Alice Azure

It was September of 2012 in Milwaukee. A group of us were packed into a van on our way back to our hotel from the opening ceremonies of Returning the Gift. Maurice Kenny was sitting right behind me in the van, driven by a young man intent on, it seemed, hitting every pot hole in the road. Maurice’s hot coffee was splashing all over him and on me. I offered to hold the cup, thinking I could better control the hot liquid. By the time we reached our hotel – the floor of my side of the van was very wet, and the coffee gone.

We had a good laugh over the incident. Still, it hadn’t dawned on me that this was Maurice Kenny, a name I heard often but had never connected to the coffee-holder that night. In the hotel lobby, I joined a free-wheeling conversation between Joe Bruchac, Geary Hobson, Philip Red Eagle, Denise Lowe and the coffee man—introduced to me as the one and only Maurice Kenny. Oh boy! I was all ears! I did my best to listen to all of them. Once back in my room, I read through the program, delighted to see that Maurice was going to be a prominent part of our festivities.

He had several of his books for sale at RTG. I asked which one was his favorite, to which he immediately responded, Tekonwatonti: Molly Brant. So I purchased that volume as well as Penelope Myrtle Kelsey’s awesome overview of Kenny’s body of work, Maurice Kenny: Celebrations of a Mohawk Writer. He wouldn’t autograph this volume until Penney had signed her name. Then he wrote, “Alice, excuse having my coffee burn.”

I cannot explain why my heart is so captivated by this poet and writer, or why I feel so drawn to him, why I have felt so bereft by his leaving before I could get to know him better. Perhaps I knew he had mentored another Mi’kmaq writer—the late Lorne Simon. Perhaps the hot, stinging, aromatic coffee spilled over me that autumn night was a burning, unforgettable blessing—a good sign. We’la’lin.

Alice Azure’s work has recently appeared in Yellow Medicine Review, Cream City Review, About Place Journal, Dawnland Voices: An Anthology of Indigenous Writing from New England, and Against the Current. Her chapbook, Worn Cities, was released in October of 2014 and awarded recognition in 2015 by Wordcraft Circle of Native Writers and Storytellers. Far from her Mi’kmaw country, she lives in the St. Louis Metropolitan Area and is a member of the St. Louis Poetry Center. More of her work can be read at www.aliceazure.com. Along with many other Mi’kmaw humanists, poets, lawyers, educators, artists and writers, her work is archived at Tepi’ketuek, http://mikmawarchives.ca.

Joseph Bruchac

WHERE THE STRAWBERRIES ARE ALWAYS RIPE–A Few Thoughts About Maurice Kenny

Maurice was a dear friend of mine for more than four decades. Not that it started all that well.

We first met through his writing when he submitted some of his poems to my literary magazine, The Greenfield Review, back in the early 1970s. I rejected his first two submissions–which prompted him to write a letter to me informing me he was no longer going to submit to our publication because whenever he was rejected twice in a row, it proved to him that particular editor did not care for or understand his work. Therefore he would not longer waste his time or his postage.

That was, I would discover, typical of Maurice– passionate about writing (whether his own or that of others), and totally unafraid to challenge anyone and speak his mind. I wrote back to him that I actually would welcome further submissions and that, despite my first two refusals, I thought his work was excellent and highly publishable. I simply had run out of space and was trying to avoid building up a backlog.

The result of my letter was that he immediately sent a thick packet of more poetry—and that I did accept what would be the first of many Kenny poems, not just in my magazine but also in anthologies I later edited, such as Songs from This Earth on Turtle’s Back, The Native North American Literary Companion, and Returning the Gift.

Maurice was a powerful editor in his own right. He was the kind of editor any author loves to work with–committed to literature, an intelligent and helpful critic, and unfailingly generous.

Maurice would, in fact, eventually become one of my own editors–publishing my poetry in Contact II, in anthologies he edited and in chapbooks from his Strawberry Press (which he first planned to call Orenda Press, but changed the name because he realized that word “Orenda” was too sacred for him to use in that way).

Maurice deeply respected traditional culture. He celebrated the history and culture of the Haudenosaunee, the Iroquois nations from which his own Native ancestry—Mohawk and Seneca– came.

He loved the native lands of upstate New York with a passion that was expressed so eloquently in his best poems. He didn’t just speak of the animals and birds, the rivers and streams, the rocks and the trees, he sang and joined his spirit to them.

When I first met Maurice in person–at an event in NYC where we were both reading (it may have been American Indian Community House)– I was surprised that he was not physically larger, that he was a short, seemingly elderly man with receding hair and a white pony tail–a persona unlike the one projected by his poems and his correspondence. (And, by the way, in all the decades I knew him—he never seemed to grow older. Year after year, he still looked and sounded the same.) However, when he took the stage to read, his powerful voice and his presence added several feet to his height.

Whenever Maurice read, he quite literally blew people away. I was with him on more than one occasion when he was one of several poets reading and the “important, featured” poet asked Maurice to go first, even after Maurice said “You really do not want me to go first.” And when Maurice left the stage and the important poet invariably said “My God, how can I follow that?” Maurice would always reply, with a little gleam in his eye, “I told you that you shouldn’t have me go first.” (Whenever we did readings together, because I always began my part with a traditional Native song, it was understood that I’d start things out. Lucky for me!)

As I write this I realize how very much I miss him, could write about Maurice, how many stories I could tell about him. Maurice was, literally, the stuff of legend.

He was also one of the most giving and generous people I’ve ever met, especially to his many students (who worshipped him) when he taught at such schools as North Country Community College and the University of Oklahoma (where he became a fanatical fan of Sooners football). And wherever he was, Maurice was a supporter of literature. Nathalie Thill, the Director of the Adirondack Center for Writing, credits Maurice’s efforts on the then fledgling center’s behalf with a vital role helping the development of the organization and its very successful programs of workshops and readings by regional writers.

Yet Maurice was always saying such things as “You wouldn’t like me if you really knew me,” and “I am a really nasty person.” In truth, he did not, to use an old cliche, suffer fools gladly. He was always ready to respond, to confront, to challenge the pretentious, the racist or sexist. He hated intolerance, both celebrated and lived diversity.

Few editors did more to encourage and publish what became known as multicultural literature and he especially championed Native American writing. The list of American Indian writers Maurice taught, published, befriended, and supported in various ways is too long to list. One of the major events that he helped plan, for example, was an amazing gathering of some 300 American Indian writers from throughout North America that took place in Oklahoma in 1992 called Returning the Gift. I doubt it would have happened without Maurice’s energy, advocacy, and involvement at every level.

I should mention that I find it hard to believe that he is actually dead for two reasons in particular. The first—as already mentioned–is that Maurice never seemed to age. He looked the same when I saw him three years ago, being honored at a Native American Poets event in Poets House in NYC as he did when we first met in person in the 70s. The second is that Maurice made an art of mortality. He was always almost dying. He had heart bypass surgery four decades ago –and not long after he left the hospital was lugging heavy boxes of books of his own and other people’s poetry to events–refusing to allow me to carry them when I was with him–while looking as if he was about to kick the bucket on the spot. It seemed as if every time I talked to Maurice over the last 40 years he had just recovered from some misfortune or another–being mugged on the stairs of the apartment where he lived in Brooklyn before moving (with his cat Sula) back to his beloved North Country. Collapsing with his head into the stove while putting food into his oven and only surviving because one of his North Country Community College students happened by and took him to the hospital. Recovering from a near-fatal bout of shingles. “I almost tasted strawberries,” he said to me each time with a smile on his face.

I remember well one winter night when, after doing a reading at Skidmore College in Saratoga Springs, my late wife Carol and I drove him over a hundred miles north—in a blizzard—for him to rendezvous with Mohawk friends in a remote cabin. When we could go no further—the access road blocked with snow and the destination still two miles away—we offered to take him to a motel ten miles back and pay for his room.

“No,” he said. “I can walk it.” Then, shouldering his bag, he walked off determinedly, pushing through the knee-deep drifts. Just before he disappeared into the swirling snow, his white pony tail the last thing visible, we heard—like a warning of impending doom–the howling of coyotes (part wolf here in the North Country and up to 60 pounds each).

“My God,” Carol said. “I can see the headline now. Mohawk Poet Eaten by Wolves.”

“Don’t worry,” I said. “We are talking about Maurice here. If anyone can get through it, he can.”

And, of course, he did. And even wrote a poem about it!

Ah, Maurice. Your road here finally did come to an end—where the Sky Road began.

And now he is there where the strawberries are always ripe. Welcomed home, I am sure, to that place beyond the sky.

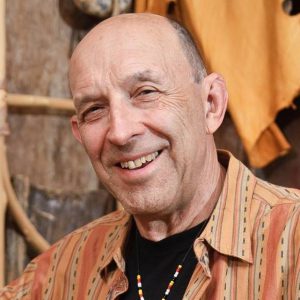

Joseph Bruchac is a writer and traditional storyteller who lives in the Adirondack Mountains Region of northern New York in the house that he was raised in by his grandparents.

Founder and Executive Director of the Greenfield Review Literary Center and The Greenfield Review Press, much of his writing draws on his Abenaki Indian ancestry. He and his two grown sons, James and Jesse, who are also storytellers and writers, work together in projects involving Native language renewal, teaching traditional Native skills, and environmental education.

His honors include a Rockefeller Humanities Fellowship, an NEA Poetry Fellowship, the Lifetime Achievement Award from the Native Writers Circle, and the National Wildlife Federation Conservation Achievement Award. Author of over 130 books in several genres for young readers and adults, his experiences include running a college program in a maximum security prison and teaching in West Africa.

Photo Courtesy of Derek C. Maus

Robert Bensen

Maurice Kenny at Hartwick College, 1996

In 1996, Hartwick College hosted “Iroquois Voices, Iroquois Visions,” a conference that drew 79 Iroquois artists and writers to the campus in Oneonta, New York, for readings, group discussions, performances, and for an exhibition in the college’s Yager Museum showing work by 58 artists. I was standing with Maurice Kenny while John C. Mohawk (a Hartwick College alumnus and recipient of an honorary doctorate) was speaking. Maurice gave a little start as if surprised, and said quietly aside, “You know, there are more us here than there are audience, but so what? We never have this kind of opportunity to get together. It means so much for us to be in each other’s company. What a force we are!”

I had the good fortune to co-edit with him the literary selections in the conference anthology, Iroquois Voices, Iroquois Vision: A Celebration of Contemporary Six Nations Arts, which was published by Bright Hill Press. The celebrated poet Bertha Rogers runs Bright Hill Press as part of the Bright Hill Literary Center in Treadwell, New York. She also was the general editor of the anthology. Maurice contributed an essay and three beautiful poems to the book, and selected poems, stories, and essays by authors John C. Mohawk, Richard W. (“Rick”) Hill, Sr., Michele (“Midge”) Dean Stock, Jake Swamp, Eric Gansworth, Lisa Fuller, Alex Jacobs, Daniel Thompson, Diane Shenandoah, and Shirlee Winder.

As part of the conference held at the college, many of us drove a half-hour out to Bertha’s farm and put on a reading and art market. It was a chilly, wet week in April, so the farm was muddy going out to the tent for the reading, which deterred no one, nor did the lateness of the sun’s arrive that morning. Maurice read from his work in the anthology and created a space for everyone to be at ease, enjoy one another’s company and appreciate how unique a time this event has proved to be.

One of the poems he gave to the anthology purports to be in the voice of the title character, the poet E. Pauline Johnson, but the lines are surely autobiographical for Maurice, or more exactly, expressive of his own spirit, certainly as it presided unobtrusively over the proceedings: “They say I am the first. Flattering / but not accurate, not true. There are centuries / of songs and singers before me. I’m one of many” (Voices, page 65; reprinted from Teonwatonti: Molly Brant, White Pine Press,1992). He spoke then, and he continues to speak, as one of the many, and for the many as well.

Robert Bensen has published five volumes of poetry, most recently Orenoque, Wetumka, and Other Poems (Bright Hill Press, 2012). He’s the editor of Children of the Dragonfly: Native American Voice on Child Custody and Education (Univ. of Arizona Press, 2001), the first anthology of literature on the subject. He is the author of Native American and Aboriginal Canadian Childhood Studies (Oxford University Press bibliographies online, 2012). His poems have been widely published in the U.S., Asia, the United Kingdom, Caribbean, India, and in Native American and African American journals. He has been awarded a National Endowment for the Arts Poetry Fellowship, the Robert Penn Warren Award, the Harvard Poetry Prize, two National Endowment for the Humanities Fellowships, and others. He is Director of Writing and Professor of English at Hartwick College, Oneonta, New York.

Robert Bensen has published five volumes of poetry, most recently Orenoque, Wetumka, and Other Poems (Bright Hill Press, 2012). He’s the editor of Children of the Dragonfly: Native American Voice on Child Custody and Education (Univ. of Arizona Press, 2001), the first anthology of literature on the subject. He is the author of Native American and Aboriginal Canadian Childhood Studies (Oxford University Press bibliographies online, 2012). His poems have been widely published in the U.S., Asia, the United Kingdom, Caribbean, India, and in Native American and African American journals. He has been awarded a National Endowment for the Arts Poetry Fellowship, the Robert Penn Warren Award, the Harvard Poetry Prize, two National Endowment for the Humanities Fellowships, and others. He is Director of Writing and Professor of English at Hartwick College, Oneonta, New York.

Geary Hobson

Maurice Kenny—A Remembrance

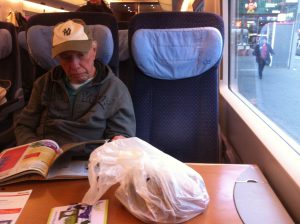

It didn’t come as a surprise at all for us who knew Maurice in those days when he was publishing his books of poetry that he issued a work with the revealing title, Greyhounding This America. For Maurice, traveling was the Greyhound bus, and did he ever use it!

I first met Maurice in the mid-70s when he came into Albuquerque—via Greyhound—to meet me and others for the first time, and to meet those he had already met on some of his previous long bus-bound trips. In this time period, contemporary Native American literature was just coming into a new prominence that, although it had been around for centuries, was now expanded and proclaimed in ways that it had never known before. During this time, the heyday of the little magazines and small presses all over the U.S. and Canada, Native American literature was coming to a new focus and proving that it was more than just the token handful of Native writers who would sometime be allowed to be featured in the mainstream mags of the day and the fledgling samey-samey anthologies, all usually New York big-press-produced. By around 1975, those of us in Albuquerque, publishing our Four Directions, Americans Before Columbus, New America, Red Earth Press, and La Confleuncia—featuring the work of Simon Ortiz, Laura Tohe, Paula Gunn Allen, Leslie Marmon Silko, Barney Bush, Joy Harjo, Ron Rogers, Luci Tapahonso, myself, etc.—we were becoming aware that much the same was being done in the Bay area, with Wendy Rose, Carol Lee Sanchez, Gerald Vizenor, etc.; in South Dakota, with Brother Benet Tvedten’s Blue Cloud Quarterly; in the Oklahoma City-Norman area with Lance Henson, Gus Palmer, Norman Russell, Russell Bates, Hanay Geoigamah, etc.; the Vancouver area, with Jeanette Armstrong, Greg Young-Ing, Maria Campbell,etc.; and in the New York-Quebec region with Joseph Bruchac, Peter Blue Cloud, Ray Fadden, John Fadden, Rokwaho, Karoniaktatie, Diane Burns, and Maurice himself, with such venues as the Greenfield Review Press and journal of the same name, Akwesasne Notes, and Maurice’s creations, Dodeca/Contact/II, and Strawberry Press. Aside from the occasional trips to other areas—Simon and Paula going to the Bay Area for a while, Joe Bruchac to Albuquerque and Oklahoma City, and variants of these—it was that short, blue-eyed Mohawk with the immense and raucous laugh who did the most to bring all these regions and writers and publications together in a true sense of brotherhood and sisterhood, as he would show us Albuquerque-ites copies of Akwesasne Notes and Contact/II, and of Blue Cloud Quarterly, and doing the same in the other afore-mentioned regions, linking us up then in ways more profound and engaging than we could have imagined at the time. All of this, long before the internet. And, all along and at the same time, he was writing his own poems, adding up to some twenty books and more. I’m pretty sure that all whom I mention here, and many others, have their Maurice stories, too.

I once referred to Maurice as a Pied Piper of Indian literature as he traveled the country, linking all together. And just about always his mode of travel was the Greyhound bus. I don’t think he ever learned to drive in his life, but, living most of his life in very urban Brooklyn, why should he have? So, along with all his other twenty-plus books, why not one with Greyhounding in the title? I rode the Greyhound a great deal in my four years of Marine Corps service, but nothing like the way Maurice did in his lifetime. And since I’m bringing it up, I think Greyhound should award Maurice a posthumous award for the service he gave them. As well, we who survive him should be ever grateful for the service that he gave to all of us who were his friends and comrades-in-print. We will keep a fire for you, Maurice.

Geary Hobson is the editor of The Remembered Earth: An Anthology of Contemporary Native American Literature (1979) and The People Who Stayed: Southeastern Indian Writing After Removal (2010), author of Deer Hunting and Other Poems (1990), The Last of the Ofos (2000), a novel, and Plain of Jars and other Stories (2011). He has published poems, short stories, critical articles, book reviews, and historical essays in numerous literary journals.

Geary Hobson is the editor of The Remembered Earth: An Anthology of Contemporary Native American Literature (1979) and The People Who Stayed: Southeastern Indian Writing After Removal (2010), author of Deer Hunting and Other Poems (1990), The Last of the Ofos (2000), a novel, and Plain of Jars and other Stories (2011). He has published poems, short stories, critical articles, book reviews, and historical essays in numerous literary journals.

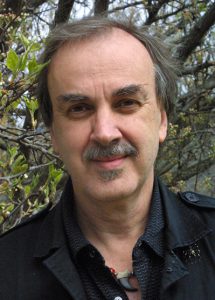

Béatrice Machet

Here is the testimony of a French girl who from the age of ten, because she couldn’t stand watching “western movies” while her schoolmates so much enjoyed them, knew she was bound to learn more and go deeper and dig out this strong feeling of embarrassment when it came to “believing” the mainstream representation of “Indians”. She was very aware that what she saw was a misrepresentation, a tissue of lies, fibs and propaganda. The woman I became has no explanations to give. I’m not “proud” of it, it’s just what happened, and it’s part of my life story. But I’m glad this awareness dawned on me because it drove me to meet such beautiful people and cultures and my mind was definitely changed through this “journey” of discovering the truth about the Native American cultures and history, from their own point of view and with their own words. I’m no ethnologist, no anthropologist, not pretending I’m “Indian” in spirit, not willing to make a career exploiting some fashionable “Indian stuff”. I’m just a poet—meaning a citizen of the world, a female artist involved in writing and translating, and as such I dedicate some of my time to contemporary Native American poetry and their authors, which proves to be a tremendously enriching human experience.

The first time I read Maurice’s poetry, I immediately enjoyed his bitter-biting-warrior-like-humorous tone. Then I read his fierce short stories, his novels, and I promised myself that sometime I would be in touch with him. The first time I met Maurice, I picked him up at the Geneva international airport. He was coming from Austria and even though he had gone through health troubles more than once, he fancied he was strong enough to drop by the French Jura mountains for a while in order to spend time with the strange French poet who tried her best to translate into French and spread the contemporary Native American authors’ works. I found him sitting on his suitcase at the top of escalators, his wide open eyes full of something like wonder. I knew he was eighty two years old, but I thought for myself that I was in front of a very sensitive child! The first eye contact was warm, genuine, absolutely welcoming. And his first appreciation, his first feeling was: “I can tell you love people from your smile.”

This couldn’t have happened without a hint of magic, a hint of luck, a hint of boldness and even of unconsciousness … but thanks to Joseph Bruchac, I succeeded in being in touch at first with authors such as Gerald Vizenor, Deborah Miranda, Carter Revard … and Maurice Kenny (later on I would meet and collaborate with many more Native American writers). We started a correspondence and gradually began to share more than mere poetry information or news about coming-up books. He told me about his life in the Adirondacks, his professional relationships with students, and the truth is he loved teaching, he loved the youth. And from discussions I learned to see and understand the many facets of his personality. We had mail exchanges long before the opportunity to meet in person occurred. Maurice had explained his preferred mean of transport to me, he was fond of Greyhounding, and had confessed he didn’t like the idea of flying, so he waited till his eighties before realizing he had never visited Europe … He overcame his fear in 2011 and 2012, to my delight of course!

After I picked him up in Geneva, we had to endure a two hour drive through the Jura mountains before arriving back at la maison de la poésie transjurassienne where I was granted a five-month writer’s residency. During this trip Maurice told me about his dearest disappeared friends; his few struggles with publishers; he spoke about his parents and his childhood; his habit of skipping classes after his parents separated; his relationship with his father after he was brought before a juvenile judge (his father came to take him from his Seneca mother); he told me about Wendy Rose and Diane Burns; about James Welch and Joseph Bruchac; about Joy Harjo and Linda Hogan; about his helpful friend Derek C Maus; about his two elder sisters; about his poor health; etc … He couldn’t stop telling stories, and it was just wonderful! He spent four days with me and offered a reading to La Maison de la Poésie. He was amazed by our French cooking. He was thrilled by a couple of elderly people who had been married for 60 years but were still demonstrating care and tenderness to each other as if they were newly weds, this made him laugh and laugh and laugh with joy and affection: “they are in love, they are in love,” he said merely. Curious, he also asked me to translate his questions to local people in order to know about their farmer lives, about their childhood during WW II, about how they felt as a community in this small village. He seemed to be driven at drawing lessons out of everything that was said. And people were very keen to confess things to him, a “stranger”, and this is how I came to know about some “secrets” in some eighty something wives’ tales!

I still can hear his voice when he was so beautifully reading his poems, I still can feel the joy and strong emotion we both felt together in Namur (Belgium, 2012) and especially in a library, when the people attending the poetry festival there, ended in understanding the ordeals the Haudenosaunee (Iroquois) that people and all the tribal nations of America went through during the more than five hundred years of colonization and genocide, acculturation and stolen children, women sterilized and so on and so forth … in the name of god (the unique and only god whose son landed on earth to save human kind), in the name of so called progress which happened to become a god as well … I swear we had tears in our eyes for real! I still can hear the two Canadian guys who came from Paris (where they finally settled) to listen to Maurice, whose words I translated into French. These two persons, who just discovered that their grandmothers were born Mohawks, were upset and revolted with the idea that this part of their ancestry was to be hidden, seen as a stain on their “almost white” identity. These events and striking encounters made together wove a sincere bound and particular friendship.

I was sometimes amazed by statements he made. One night he was about to go to bed and with a very concentrated look he said: “well you know poetry nowadays has no place and so little impact in this world, but please keep writing, keep translating, keep reading. It’s the best thing you can do because doing so you’re obeying some greater reality, you’re listening to spirits.”

After Maurice’s “I’m the Sun,” a long poem which paid homage to the native American people and the members of the AIM occupying the site of Wounded Knee in 1973, I cannot but try to imagine what he would have written to pay homage to the people on the Standing Rock reservation with all the other members of different tribes who are still peacefully praying at Canon Ball, all the water protectors, occupying the site because “Mni wiconi”! He wouldn’t have kept silent.

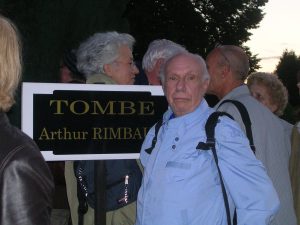

In order of apparition in my memory, he first was the-one-who-wrote-Tekonwatonti-Molly-Brant, the-one-who-wrote-I-am-the-sun and many other books I would later read thanks to Maurice’s generosity: he provided all his available books for me. He also was the-one-who-sent-Adirondack-berries-jam, the way I was the-one-who-sent-fig-jam to him. He was the-one-who-introduced-me-to-James T Stevens’s poems which I loved and I even translated a few for a French poetry magazine. But he could also have been known as The-one-who-so-much-admired-Louise Bogan… etc, etc. To me, Maurice will remain forever the-one-who-had-the-goosebumps-when-walking-near-a-church. He really almost fainted when we had to cross a square where a big Catholic church was erected, in order to be on time at a poetry reading. This is how I came to truly understand the traumatisms and wounds that Native American people endured, beyond a possibility of healing, and I felt so impotent at this very moment…

I would like to evoke his poem PONTIAC as follows:

Pontiac

Retrieving my past?

I hadn’t known

I had lost it

My footprint is still there

on fallen leaves, on cleared ground

My scent is still upon the river

where I bathed each morning

My words are on the wind

echoing through pine

My blood is in the loins

of my sons and daughters

My flesh is there . . .

it is the earth . . .

you now walk upon it, you now take harvest from it:

the corn you eat,

the tomato seed you plant,

the tree that shades,

the deer-skin that warms your coldness

I wrap you

I sing you

I blood you

I am stronger now than ever before

I am many

My war cry is loud

you hear it

I am many

I am the broth of your soup

I am the hawk on the elm

I am the leather of your boot

I sing you

I blood you

Tell this to the scholar

Tell this to the historian

who chronicles

Tell this to the general

who believes me dead

I sing you

I blood you

I am the bone of your thought

And I’d like to follow this poem and adapt it to the new struggle:

Black Snake

Ignoring the prophecy?

I hadn’t known

I had forgotten it

Evidences are still here

such as a golden eagle and

buffalos coming to the camp

speaking for the ancestors

Their words are on their breath

and feathers showing their will

Their blood is in the loins

of their many sons and daughters

gathering here . . .

honoring the earth . . .

protecting the water the next generations will drink

protecting life itself

running through the veins

of your mother

quenching the trees’

the animals’ thirst

water wraps you

sings you bloods you

heartbeats you

is you

We are stronger now than ever before

we are many

our peaceful sacred war cry is loud

you hear it

we are many

Water is sustenance is purity is fertility

water is the on-going flowing

water is continuity

water sings you bloods you

heartbeats you

Tell this to the engineers

Tell this to the shareholders

to the officials

Tell this to the policemen

who try to stop and blind us

water wraps you

sings you bloods you

heartbeats you

is the core of your thought

Yes, Maurice in many ways will remain the bone of my thoughts and his past, his numerous books won’t be “retrieved,” nor ever withdrawn, and he will not be forgotten, so nothing of his passage on earth can be lost.

Béatrice Machet is the author of 12 poetry books in French, two in English. She is used to collaborating with artists from all kinds of disciplines such as painters, sculptors, musicians, composers, video-makers, dancers and choreographers, and with whom she performs her poetry. She has had writer residences, leads creative writing workshops, is called for teaching and performing in schools and colleges. She translates many Native American contemporary poets into French and managed to gather and get anthologies of Native authors published in France.

Béatrice Machet is the author of 12 poetry books in French, two in English. She is used to collaborating with artists from all kinds of disciplines such as painters, sculptors, musicians, composers, video-makers, dancers and choreographers, and with whom she performs her poetry. She has had writer residences, leads creative writing workshops, is called for teaching and performing in schools and colleges. She translates many Native American contemporary poets into French and managed to gather and get anthologies of Native authors published in France.

Maurice at Rimbaud’s Tomb. Courtesy of Beatrice Machet