Derek C. Maus

“Mastery”

If ever word there was that needed rescue

From overfoul connotation, it might well be this:

Master.

From Tom Waits’s Renfield shouting it slavishly –

“May-aaaaaasss-tuh!” –

at Gary Oldman’s draconic Dracula,

To Simon Legree’s “bad cop” juxtaposed against Augustine St.

Clare’s ostensibly “good cop”

It’s not easy to feel much comfort at being told one is in

the presence of one’s master any more.

But perhaps that’s not as it should be.

For as writers, as thinkers, as people with living hearts and minds,

we often must stand on the shoulders of giants to see over the

fences and walls that block the paths before us.

And if those shoulders are to support our often halting and fearfully

untutored weights, bearing down like unhewn logs or unchiseled

stone, then it appears to me there needs to be some power in them.

My fortunate soul has known such power

– perhaps not often, but also not never.

Some of my giants may even stand no more than five-foot-eight –

even if the New York DMV robs them of an official inch or two.

Eliot ripped off Dante and called Pound “il migglior fabbro”

as he started his journey through the waste-land

Even though my landscapes have never been as cruel as those of

Eliot’s Bavarian April and my lilacs have usually

– usually – bloomed of their own accord

I will not call him by this name, though I esteem him in

measures no less profound.

Master of strawberries, wild and tamed,

master of chanted and enchanting moccasins

master of dugouts and Greyhound buses:

You redeemed the word as verily as the

striving shoot of trillium redeems the winter.

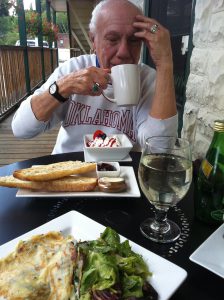

*Header Photo, “Maurice in Namur,” Courtesy of Beatrice Machet

Derek C. Maus is Professor of English and Communication at SUNY Potsdam, where he has taught all manner of other people’s literary beauty and brilliance since 2001. Three days after starting his job there, he met Maurice Kenny — whose office was two doors down the hall — and quickly struck up a friendship that involved shared meals numbering into the thousands, travels through a half-dozen countries on multiple continents, spirited argument about the merits (or lack thereof) of various artists and their works, the ardent affections of numerous dogs and cats, and above all a mutual appreciation for the trilliums, cherries, homegrown tomatoes, and linden trees that help mitigate the pain of being surrounded by human ignorance. An additional tribute he has written to Maurice Kenny can be found here.

Derek C. Maus is Professor of English and Communication at SUNY Potsdam, where he has taught all manner of other people’s literary beauty and brilliance since 2001. Three days after starting his job there, he met Maurice Kenny — whose office was two doors down the hall — and quickly struck up a friendship that involved shared meals numbering into the thousands, travels through a half-dozen countries on multiple continents, spirited argument about the merits (or lack thereof) of various artists and their works, the ardent affections of numerous dogs and cats, and above all a mutual appreciation for the trilliums, cherries, homegrown tomatoes, and linden trees that help mitigate the pain of being surrounded by human ignorance. An additional tribute he has written to Maurice Kenny can be found here.

Suzanne Rancourt

Who Strings the Bow

The poem “Who strings the bow?” was written when I lived in Redford, NY and I was attending a writing workshop with Maurice at North Country Community College in Saranac Lake. The poem is a true account about my youngest son. Maurice really loved this poem which I wrote probably around 1988. My youngest son graduated from high school in June 2002 and began his undergrad studies at SUNY Potsdam. One day he mentions that he is taking a writing class with a Maurice Kenny. I gave my son a copy of the poem and asked that he please share this with Maurice as I wrote it in one of of his classes. I also asked that my son tell Maurice that he is the boy in the poem. Maurice took my son under his wing and really helped him out. Maurice was like that.

he pulls two chairs to the table.

lunch time, the sky

is still grey. a steady garden rain hangs in the pines

before it is gravity-sucked into the earth.

everyone must be fed

and the plush nose of Blackie

the velour puppy

is placed lovingly inside

a Raggedy Ann + Andy lunch box

her thermos

a 3-D viewmaster, filled

with fluid glimpses of Sesame Street.

he is five, my son, and says “I love you, Mom,

but I can’t tell you this” and raises

his flapping-Raven-wing-eyebrows

four times. he pats

the pseudo-ravioli with a clean spoon

swirls the red sauce and spiraling cheese

“Mom, is it possible

to be a bow and an arrow

at the same time?”

Suzanne Rancourt is this issue’s featured writer.

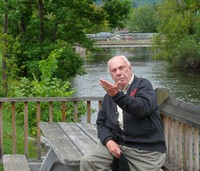

Kenny at Saranac Lake. Courtesy of Phil Gallos.

Wendy Rose

Leaving Port Authority for Akwesasne

New York City, 1985

I saw a mesa

between two buildings,

a row of tall

narrow houses,

bare as the desert I know,

the roofs appearing

in clumps like greasewood.

O Wendy, he said

looking at his fingernails,

that’s Weehawken.

One way or another

we’ll get somewhere soon

for I have seen crows

dance on Manhatttan snow,

a hawk on Henry Street,

smoke plumes from the lips

of street kids,

mesas along the Hudson.

I am getting ready.

What the Mohawk Made the Hopi Say

Somewhere in the Adirondacks, January 1985

Unaccustomed to breath

frozen so still

as to crackle

from nose to lip,

I search the birches

for a squirrel’s tail jerk,

the roadside pond

for quail or swan.

Or is this that famous sleep

they speak of with fever in the east

or up in the mountains

when the words just yawn

and settle on their hands?

Tell me again

I have no winter at home

and the tongues that lap

against my bones

bear no leaves.

Bless this tongue

in your special way,

make brittle the spit

and faceted the tear,

make diamonds

from turquoise,

crystal light

to illumine your ice.

I finally agree

turning into a rock

that these are mountains

noble as any

and all of Arizona

must wait

for spring thaw.

Poems from What the Mohawk Made the Hopi Say, a collaboration between Maurice Kenny and the Wendy Rose. Used with permission of Wendy Rose.

Wendy Rose is of Hopi, Miwok, and European descent. A writer and poet, she is the author of thirteen poetry collections , including Academic Squaw: Reports to the World from the Ivory Tower (1977); What Happened When the Hopi Hit New York (1982); The Halfbreed Chronicles and Other Poems (1985); Lost Copper (1980), which was nominated for a Pulitzer Prize; and Bone Dance: New and Selected Poems 1965–1992 (1994). Her poetry has been in over 150 anthologies. In addition to poetry, Rose writes nonfiction, often addressing issues of appropriation of Native American culture, including “whiteshamanism,” the misuse of the shaman identity by white writers.

Wendy Rose is of Hopi, Miwok, and European descent. A writer and poet, she is the author of thirteen poetry collections , including Academic Squaw: Reports to the World from the Ivory Tower (1977); What Happened When the Hopi Hit New York (1982); The Halfbreed Chronicles and Other Poems (1985); Lost Copper (1980), which was nominated for a Pulitzer Prize; and Bone Dance: New and Selected Poems 1965–1992 (1994). Her poetry has been in over 150 anthologies. In addition to poetry, Rose writes nonfiction, often addressing issues of appropriation of Native American culture, including “whiteshamanism,” the misuse of the shaman identity by white writers.

Alan Steinberg

When the Coyote Howls

I won’t know where or when

for now there is silence

in the empty air

a grey stillness

that swallows the sun

like dry earth

swallows the rain

But it will be at night

under a yellow moon

hung like a pendant

on a chain of stars

Thin and gaunt

it will lift its head

in the barren field

and with a voice

ripe with hunger

make the darkness shudder

and all the silent

living things

cry out in blood-red wonder

He Sang for Us All

In a deep voice

as if out of a cave

where all the joys

and sorrows

had been laid to rest

like the bones

of the long lost dead

He sang for all of them

the natives of every

time and place

sparrow and hawk

lion and lamb

Custer and Sioux

fathers and mothers

with dreams

and rifles and bos

This is life

he sang

one hand open

one hand clenched

in a fist

eagle high

on a mountain

snail in a reef

And every lover

he sang at the end

waving goodbye

with tears

and a grin

Alan Steinberg works at SUNY Potsdam. He has published fiction (Cry of the Leopard, St. Martin’s Press), poetry (Fathering, Sarasota Poetry Press), and drama (The Road to Corinth, Players Press).

Alan Steinberg works at SUNY Potsdam. He has published fiction (Cry of the Leopard, St. Martin’s Press), poetry (Fathering, Sarasota Poetry Press), and drama (The Road to Corinth, Players Press).