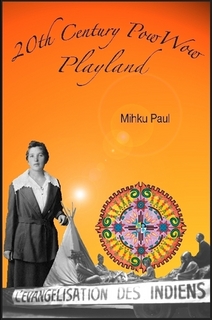

It’s a beautiful thing that Bowman Books is now publishing regional Native titles  faster than I can review them. I had been eagerly awaiting Mihku Paul’s first book of poetry, and it’s now out: 20th Century PowWow Playland. You can order it here.

faster than I can review them. I had been eagerly awaiting Mihku Paul’s first book of poetry, and it’s now out: 20th Century PowWow Playland. You can order it here.

Paul is Maliseet, an enrolled member of the Kingsclear First Nation in New Brunswick, though she grew up in Maine, near Penobscot homeland, and lives now in Portland. She’s a visual artist as well as a poet, doing colorful medicine wheel paintings like the one on the cover of 20th Century PowWow. She did an MFA in creative writing at Stonecoast, and an exhibit for the Abbe Museum in Bar Harbor, which is where I first heard of her. “Look Twice: the Waponahki in Image and Verse” juxtaposed some of her most powerful poems with historic photographs of Wabanaki people from Maine and the Maritimes.

It was a pleasure to watch this book grow; if you have any opportunity to invite Mihku Paul to your school or library or other venue to give a reading, she’s a magnetic performer. The poems from “Look Twice” are carefully amplified and revised in this sparkling volume (given extra gloss, I’d like to note, by a UNH PhD student, Michael LeBlanc, who is really a remarkable editor). The ordering is striking. The first poem, “Echo of Multitudes” begins in Maliseet homeland, the Wolastoq (St. John River) watershed: “Picture this. Great rivers snake through a forest; water road, traversed in season, straining and/swollen at ice out, moving endlessly to the sea.” Paul returns again and again to the river motif; along the way, she moves between imaginative reconstructions of her ancestors’ lives, and grittier explorations of contemporary realities: racism, suicide, community trauma.

I love many things about these poems: their sheer music, their incandescent colors. But I think one thing I love best, having seen “Look Twice,” is how Paul can seem to liberate the spirits within an image. The old photos she has studied so lovingly can seem, as she says in the collection’s title poem, colonized and frozen by the “rigid lens of history, a dangerous weapon.” But the poet has such imaginative empathy, such strong identifications, with those figures that she suggests a very strong sense of a Wabanaki “we.”

Mihku Paul maintains her own website where you can learn more; if you have any taste for academic reading, I published an essay on her poetry and Alice Azure’s earlier this year in MELUS: Multi-Ethnic Literatures of the U.S..