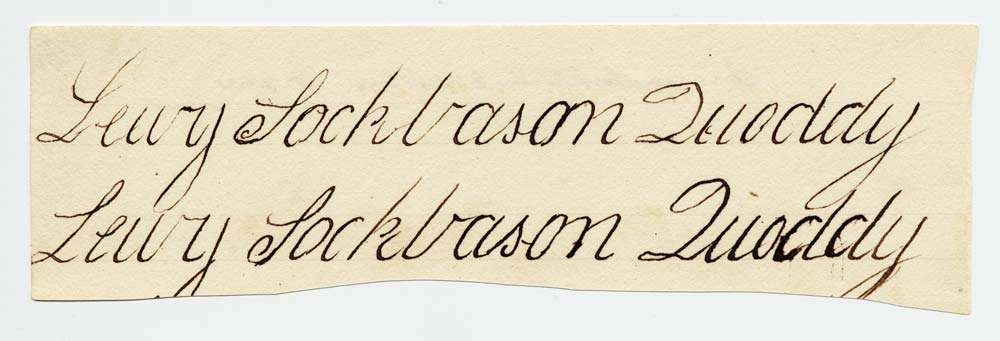

Last night, at the Windows on Maine site, I ran across this early-19th-century penmanship sample from a 15-year-old Passamaquoddy student, Lewy Sockbason:

The sample is tucked into an 1828 report from the Reverend Elijah Kellogg, a Protestant missionary who ran a school on the Pleasant Point reservation for six years. Kellogg was much enamored of Lewy’s father, Deacon Sockbason, whom he considered one of the “good Indians” willing to embrace “civilization.” Deacon Sockbason, of course, was more complicated than that. Often recalled as the first man to live in a wood-framed house at Pleasant Point, he was literate, and fluent in English, French, and Passamaquoddy. Tribal historian Donald Soctomah says that Sockbason worked on a number of important negotiations for the Passamaquoddies.

To get at early Native American writing (like the Lewy Sockbason penmanship exercise), you often have to go through white missionaries, administrators, and agents; which is usually a depressing venture, because it flushes out so much racism, subtle and not-so-subtle. William Henry Kilby, whose 1888 Eastport and Passamaquoddy: A Collection of Historical and Biographical Sketches has (inexplicably) gone through several reprintings, met Deacon Sockbason, and says:

He could read and write, though his spelling, as shown in the sample in my possession, was rather imperfect; and he had been to Washington to see the President. He considered himself the greatest man in the tribe, and was continually trying to impress others with the idea of his dignity and importance. On special occasions, he wore a coat of startling style. Years ago, on one of my visits to Pleasant Point, looking over the fence of the little burial-ground I saw a rift of split cedar standing in place of a headstone, bearing in rude letters the inscription, — TIKN SOKEPSN.

This has been on my mind for the last 24 hours: the “rude” lettering on the allegedly uppity senior Sockbason’s grave, set against his son’s exemplary penmanship, circulated as an example of successful “civilization.” The nasty assumptions about why Indians should or should not write, and where and how they got it wrong; against the real reasons Indians pursued literacy, and where and how they got it right.

The Passamaquoddy reservations in the 19th century (and later) were grievously poor, because, as the Abbe Museum explains, the state of Maine–illegally, and continually–sold off and leased tribal lands and resources without distributing the profits to Native people. Those resources included timber, a theft routinely protested–in writing–by Passamaquoddy leaders including Deacon Sockbason, and later Lewey Mitchell, the tribal representative to the state legislature in the 1880s. Donald Soctomah’s archives include this petition from Deacon Sockbason, demanding that the State stop depleting fish and timber and return Passamaquoddy lands:

Your friends further state that they are in great want of a piece of woodland for the purpose of getting wood in the winter for the use of the elderly Indians, their women, and children, as they live on a point of land called Pleasant Point where they cannot procure wood, as all the woodland for the distance of thirty miles is owned by private individuals.

Not exactly the words of a tool of the colonial powers. The fact that Deacon Sockbason lived in a wood-frame house, then, was not what his white neighbors thought. Settler colonists including William Kilby and Henry Thoreau were unnerved by literate Indians in wood houses: they found such people pitiful, tragic, assimilated. But Sockbason was clearly trying to ensure that his own people had access to their own resources. Kellogg tells a story of how the local priest tried to bar workmen from bringing a frame for a workshop ashore at Pleasant Point; Sockbason intervened, and the workshop was built.

Now I want to know more about Deacon Sockbason and his son, including how Lewy thought about his identity and homeland as “Quoddy” when he demonstrated his perfect penmanship. Sockabasins (with a variety of spellings) at Passamaquoddy have included many fine writers, including the poet Mary Ellen Socobasin and the memoirist and children’s book author Allen Sockabasin.