Last Monday, May 21, I was lucky enough to get up to Orono to see a staged reading of Donna Loring’s musical play, The Glooskape Chronicles: Creation and the Venetian Basket. I love visiting that UMaine campus: between its proximity to Indian Island and its strong Wabanaki Center, it has a vibrant local indigenous presence, and Native events like this one are well-attended, community gatherings.

In fact, this play was partly an outgrowth of a really nice collaboration between Margo Lukens, a professor in the English department, and William S. Yellow Robe, Jr., (Assiniboine), one of the preeminent indigenous playwrights working today, and a frequent writer and teacher in residence at the university. Lukens and Yellow Robe have been doing community theater with local Penobscots for a couple of years now, and out of that work, something incredibly exciting is emerging: a new literary tradition of Wabanaki drama. (In addition to Loring, a talented young woman named Maulian Dana also has a play in the works.)

One of my students guest-blogged here last summer about Loring’s impressive memoir of her years in the Maine state legislature. Now “retired,” Loring is working full-bore on writing and other media productions, through her new nonprofit, Seven Eagles (and that link is really worth visiting, because you can see a trailer of Glooskape, as well as descriptions of Loring’s other projects).

Glooskape opens on three contemporary Penobscot women at a camp deep in the Maine woods: Hazel and Georgia have moved out there to try to live more traditionally and simply; their friend Jane, a Vietnam veteran, is visiting. The women share their knowledge about the old ways, but the scenario is thoroughly modern, and the dialogue often hilarious, as the women outwit a pushy game warden (deliberately mispronouncing his name “Jeckin,” the Penobscot word for “buttocks”), and tease Hazel’s grandson Little Bear, who also comes for a visit. These visits prompt Hazel to tell creation stories of Gluskabe, the Wabanaki trickster/culture hero; when, midway through the play, she learns she is terminally ill, her storytelling takes on extra urgency.

Glooskape opens on three contemporary Penobscot women at a camp deep in the Maine woods: Hazel and Georgia have moved out there to try to live more traditionally and simply; their friend Jane, a Vietnam veteran, is visiting. The women share their knowledge about the old ways, but the scenario is thoroughly modern, and the dialogue often hilarious, as the women outwit a pushy game warden (deliberately mispronouncing his name “Jeckin,” the Penobscot word for “buttocks”), and tease Hazel’s grandson Little Bear, who also comes for a visit. These visits prompt Hazel to tell creation stories of Gluskabe, the Wabanaki trickster/culture hero; when, midway through the play, she learns she is terminally ill, her storytelling takes on extra urgency.

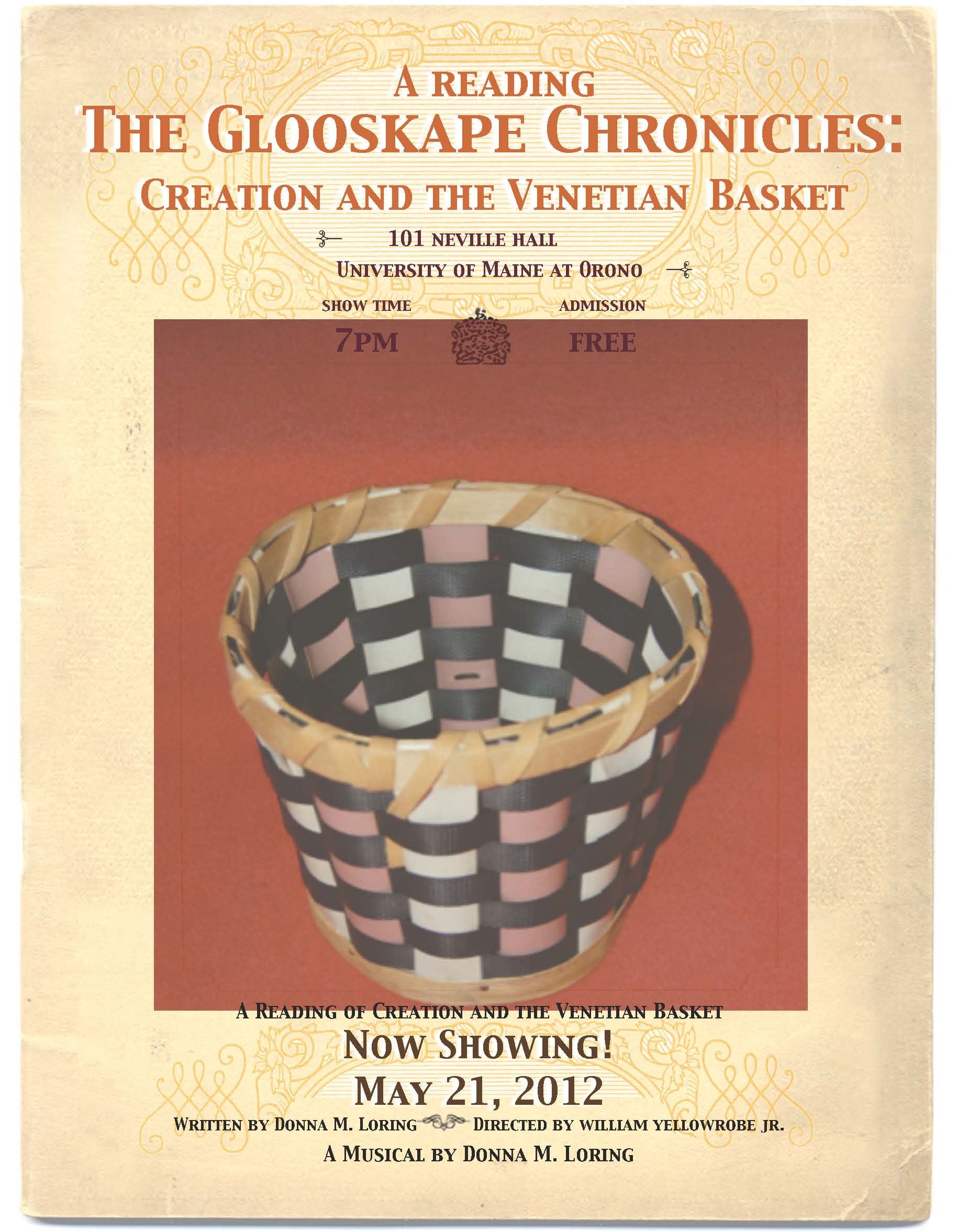

Though Glooskape is still a work in progress, and still in search of a composer, the staged reading suggested plenty of places where song and dance will enhance not only the stories, but also Loring’s innovation. During a talkback after the reading, Loring noted that in her research into the Gluskabe tradition, she learned that these stories were often sung. So she is not thinking (necessarily) of a “musical” in the Judy Garland or Glee sense, but as a way of updating and revitalizing Penobscot tradition. In this sense, Loring’s play is like the Venetian basket referenced in her title and on the poster. Made by Maliseet Medicine Man Charles W. Solomon, the basket was made out of Venetian blinds, as a comment on how Wabanaki people can adapt to a future–one in which trees are under very serious threat–while still keeping their traditions and culture alive.

What I took away from that was that this “first Penobscot musical” could shake up my expectations of musicals, of theater, and of Native American representation. . .while still being eminently, vitally Penobscot.

For news and updates on The Glooskape Chronicles, watch the Seven Eagles website!