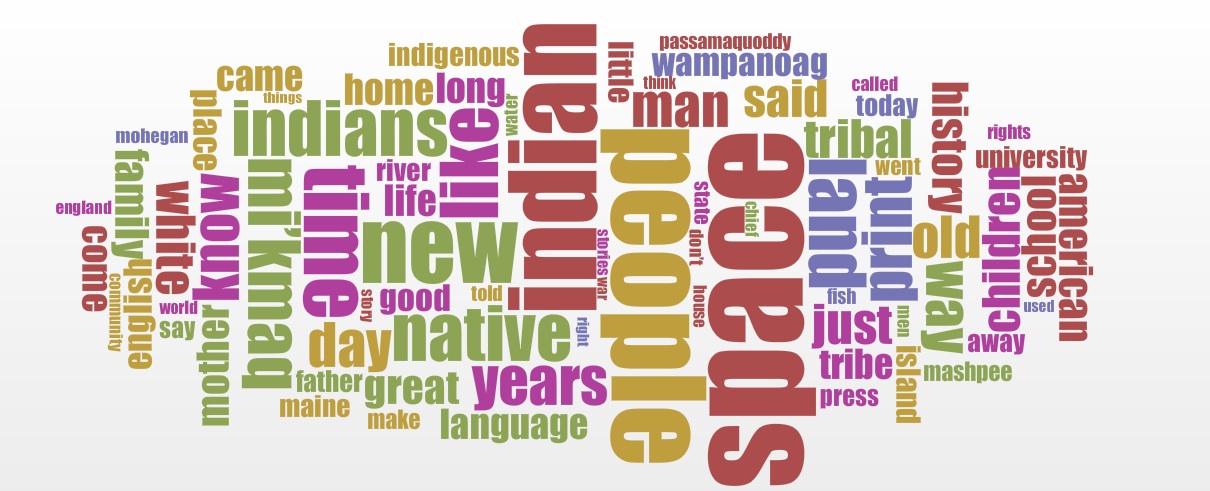

My colleague James Finley produced this word cloud by running the entire manuscript for Dawnland Voices–the 600-page anthology of regional Native writing I’ve just finished editing–through a tool called Voyant. (Click “Voyant” for a clearer picture.)

My colleague James Finley produced this word cloud by running the entire manuscript for Dawnland Voices–the 600-page anthology of regional Native writing I’ve just finished editing–through a tool called Voyant. (Click “Voyant” for a clearer picture.)

Like the tag cloud at the left (which shows only how often I have tagged particular topics on this blog, myself), this little wordle represents the most frequently-used words appearing in the anthology. Many people retain a healthy ambivalence about the usefulness of word clouds, but they’re at least an engaging prompt for conversation.

In the one above, the three largest terms come as little surprise. I do enjoy seeing “land” and “print” in the same relatively large color and size, since one of the things I’ve learned while reading a lot of this literature is that Native literature and Native land are really inseparable (an argument brilliantly elaborated in Abenaki historian Lisa Brooks’s book, The Common Pot). I also like seeing so many words that underscore the continuous presence of Native people in this region: “time,” “years,” “long,” “history,” and of course “children” and “today.” Note, too, the presence of so many terms describing kinship and community.

At first I wondered why only four tribal nations seem to have made it onto this wordle. It’s not that Mi’kmaq, Wampanoag, Passamaquoddy and Mohegan authors are necessarily better represented in the anthology, since each tribal nation gets more or less the same number of pages. But it is the case that many of the Mi’kmaq and Wampanoag writers we selected are historians. In these writings, then, they refer over and over to their people in the course of a single piece. This is a little different in, say, some of the Abenaki writings; there are certainly a lot of talented Abenaki writers, but they include a good number of creative writers–in particular, poets, who don’t always invoke the term “Abenaki” quite so often. Writers like Joseph Bruchac and Cheryl Savageau sometimes invoke their own term for homeland, “Ndakinna”; or they depict specific Abenaki places, like the Pemigewasset River.

None of that is terribly scientific, of course! [If I had to guess how “university” made it in there, it would be that James included in this wordle the bibliography for the whole book, which includes a lot of university presses–academic publishers being often (though not always) more willing than commercial ones to take care of otherwise marginalized authors.] If you’ve never tried a wordle, especially you writers: see what it flushes out of your poems or short stories.