Pushing the Boundaries: An Interview with Two New England Native Artists

Virginia McLaurin is a PhD student in the Anthropology Department at the University of Massachusetts Amherst, specializing in Native Studies and Film. Her Eastern Cherokee ancestry led to her academic focus on both dominant filmic and televisual representations of Native peoples as well as Indigenous-created productions in a variety of visual media. In addition to her scholarly work on Indigenous film and digital media, she is an amateur painter and beadwork artist.

Virginia McLaurin is a PhD student in the Anthropology Department at the University of Massachusetts Amherst, specializing in Native Studies and Film. Her Eastern Cherokee ancestry led to her academic focus on both dominant filmic and televisual representations of Native peoples as well as Indigenous-created productions in a variety of visual media. In addition to her scholarly work on Indigenous film and digital media, she is an amateur painter and beadwork artist.

Christiana Becker, a fifth year student at the University of Maine, is currently working towards her Bachelor’s Degree in Art Education and Studio Art, along with a minor in Dance. Afterwards, Christiana plans on going on to graduate school, pursuing studies in occupational therapy at the University of Southern Maine.

Christiana’s artwork was first shown through her middle school, which participated in the Wabanaki Student Art Show, a collaboration of artwork from Maine Indian Schools, and was shown at the Abbe Museum. During Christiana’s college years her artwork has been shown at Harlow Gallery in 2015, Steven’s Hall from 2015 to 2016, Lord Hall Gallery in 2015 and 2016, and the Memorial Union in 2016. Christiana has also participated in the University of Maine’s Fall Dance Show in 2012, the Fall Dance Show in 2013, and the Spring Dance Show in 2014. She has been interviewed by the Maine Journal and the Bangor Daily News about her artwork and its intersections with her Penobscot heritage.

In April 2015, Christiana participated in the University of Maine Artworks Program, where students write lessons for elementary to middle school children and teach said lessons for an hour and a half, after school on Friday afternoons. Also in April 2015, Christiana participated in the Shaw House Service Learning Project, Art and Community: A PhotoVoice Project, through her art education classes at the University of Maine. Christiana helped organize a cyanotype project along with her classmates and teacher, Laurie Hicks. Christiana’s responsibilities were to learn about the cyanotype process, research how photography has been used as a narrative, and investigate how programs have used photography within their own photovoice projects. As a group the art education class would meet with members of Shaw House once a month and talk about the aesthetics of photography, take images of Bangor, ME, edit photographs using iPhoto, and print photographs taken by members of Shaw House using cyanotype process.

Justin Beatty is a visual artist, powwow singer, and digital music maker of Ojibwe, Saponi, and African-American descent. Born in 1972, he grew up in Roosevelt, NY and was exposed to a multitude of art and music by his parents early on and began playing the drums in third grade. In the 1980s he fell in love with graffiti and became interested in graphic design. It was also at this time he began DJing with a group of friends from junior high school.

Justin Beatty is a visual artist, powwow singer, and digital music maker of Ojibwe, Saponi, and African-American descent. Born in 1972, he grew up in Roosevelt, NY and was exposed to a multitude of art and music by his parents early on and began playing the drums in third grade. In the 1980s he fell in love with graffiti and became interested in graphic design. It was also at this time he began DJing with a group of friends from junior high school.

With regards to visual art he began developing his personal style in the late 80s and began using his graffiti skills as a small commercial venture. He designed and painted custom artwork and characters on clothes (as was the style at the time) and became well-known locally for the quality of his work. In the 1990s he attended the University of Massachusetts-Amherst where he learned to develop his skills and sense of style even further. He expanded his repertoire to include clay, plaster, and metal working. It was during his time at UMass-Amherst that he was commissioned, through the Josephine White Eagle Cultural Center, to do two murals for the Native American students’ floor in the Chadbourne dormitory where he is proud to say they still hang today. After leaving the university, he began to do artwork on a more private and personal level for people by designing tattoos, logos, and creating designs for family’s, and friends’ regalia.

In 2001 he began to focus on music again which earned him steady DJing gigs in Western Massachusetts at well-known clubs and bars like Atlantis, Delano’s, and 2nd Street. It was around this time, he became a member of the band NewMerika, garnering accolades as the group’s DJ/Hype Man. In 2005, he DJed the premier party for “BET Presents – Ultimate Hustler” at Crash Mansion/BLVD in NYC. It was at this time he also started working with world famous DJ J. Period at Truelements Music, an independent record label in Brooklyn, NY. During his tenure at Truelements he worked on projects for The Roots, The Isley Brothers, Mary J. Blige, Game Rebellion, and many others. In 2007 NewMerika was nominated for a Los Angeles Music Award and in 2009 NewMerika was voted one of the Top 100 NYC Bands of the Summer. Currently crafting his first solo album of original music, he has been working with the recently founded indie label Red Dirt East. Coming full circle he recently returned to making visual art and began his foray into creating digital artwork which allows him to learn more and more about stretching the boundaries of his talent and imagination.

______________________________________________________________________________

Virginia McLaurin: Justin and Christiana, both of you are artists with Indigenous heritage from the Northeast. Do you identify with the term “Native artist,” and do you think that it’s a valuable term?

Justin Beatty: I will say that it’s a valuable term, because it identifies a perspective from which I come from and that I incorporate into my art. My culture also affects the way I view my art and other peoples’ art as well; it all comes from a perspective that integrates my cultural upbringing. I think that, in terms of the difference between the ethnic and cultural designation and the legal definition—in terms of “Native American”—that’s a little tricky. At times there’s a difference between someone’s cultural, ethnic background and the legality of the term “Native American.” But in terms of my art, that’s part of who I am, the essence of my work. It’s my cultural heritage that gave me my earliest sense of what meaning is, and what power is, and what hope is, and what survival means – all of which are things which come out in my work. So, the term “Native artist,” it’s applicable in a lot of instances and goes beyond what any individual person thinks it means… it’s not a massively useful term, but it’s not a wasteful term either.

VM: And how do you feel about it Christiana?

Christiana Becker: I feel like the term “Native American artist” or “Native American art” applies to some of my work, especially for the project I’m working on right now, but I wouldn’t think it applies to everything I do. But the pieces I’ve been doing, I feel that they directly relate to the term because I’m doing illustrations of Native American stories I remember being told when I was in school. I went to school at the Indian Island school, on our Penobscot reservation. And I’ve also done a story that was not related to my experiences—a Cherokee story—and I don’t think that that’s wrong, that I did a story that’s not from my tribe. I think it’s good to communicate that there are other tribes and their messages, the legends that they have, and that they can all come together to offer meanings. But I do a bunch of other artwork that doesn’t relate to my heritage at all. I’ve been going to art school and some of my teachers will say “hey, draw this still life” and I don’t feel like my heritage comes into play in those pieces of artwork.

VM: I wanted to ask you both, as artists who the term “Native artist” might apply to, about a famous quote by Indigenous filmmaker Victor Masayesva Jr. He once said that “there is such a thing as an Indian aesthetic, and it begins in the sacred,” but recently some other Native filmmakers like Blackhorse Lowe and Sterlin Harjo have pushed back against that and asserted that no, there really isn’t a Native aesthetic, there’s nothing we all have to have in common. Do you think that there is such a thing as a Native aesthetic in film or art? Is there something that all Native artists have in common? Or is that too limiting?

[Pause]

JB: I feel like Christiana is only letting me go first here because I’m older! I do think there is such a thing as a Native aesthetic. I don’t think it’s necessarily present all the time—an artist can choose to apply it or disregard it, or make it a major component or a minor component of their work. If you participate in your culture to some extent, whatever nation you’re from, you’ll be influenced by that environment. And the ways people operate, these cultures, are based in thousands and thousands of years of people acting as a tribe, and that includes the works they produce.

VM: And so you see it as multiple, tribally specific Native aesthetics?

JB: I would say yes, certainly more than a totalizing aesthetic… because I wouldn’t say that there’s one thing that all Native artists have. The aesthetics and even the view of art in the Southwest, for example, are different from the aesthetics of art and the way art is viewed in the Northeast. And even in the Northeast, Abenaki artwork is different than Anishinaabe artwork, you know? So the inspiration can come from an Indigenous background, and that aspect could be shared, but other than that it comes from those different tribal sources and it also depends on how much the traditional art and views of art have influenced you, how involved you are in your culture, and in what ways. Is it

limiting? I don’t think so. It’s really a stepping stone of a term, but is art ever really limiting? For myself, most of my art now is digital, and do I draw cultural items? Sometimes. But do I also draw whatever I want that has nothing to do with Indigeneity? Absolutely. Do I ever feel limited by someone saying to me, you’re a Native or Indigenous artist? No, I kind of appreciate it because I think that there are some great artists that come out of Indigenous communities. To be counted among those artists, is it worth any less than if I were to be counted among great European artists like Van Gogh or Monet? No. Why should we not be excited about that thought? I can understand the fear of being pigeonholed, but I believe there is an Indigenous aesthetic. I think there are things I find beautiful that people from another culture wouldn’t find beautiful, at least not in the same way, and there’s value in that. It means that there’s an underlying perspective, whether spoken or unspoken, that the artists themselves come from.

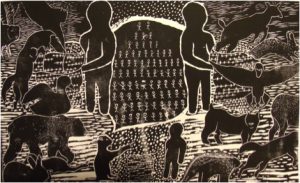

CB: I would say that I think there is a “Native American aesthetic” but I don’t know whether it needs to be used by Native artists, whether it’s necessarily wrong or right to use it. The work that I have made most recently, based on the Gluskabe stories, has evolved every year. One of my teachers was invested in giving all of the characters in these drawings personality. And she introduced me to Aboriginal art from Australia and other places so that I could see how their characters looked, encouraging me to use more of an Indigenous aesthetic but one that was Native American. However, as I worked on several pieces involving these stories I also wanted to keep the characters recognizably the same, without imposing that aesthetic too much on them. So I think it’s up to the artist how much they want to incorporate Indigenous imagery or a Native American aesthetic.

Gluskabe Captures All the Game Animals, Christiana Becker

Gluskabe Bags All the Game Animals is a Penobscot story. The story goes, Gluskabe lay down on his bedding and began to sing, wishing for a game-bag of hair, so that he might capture animals more easily. His grandmother Woodchuck then made him a game-bag of deer hair. When it was finished, she tossed it to Gluskabe; but he didn’t stop singing. Then again Woodchuck made a game-bag, but this time out of moose-hair. She tossed it to Gluskabe and he still continued to sing, wishing for a game-bag of hair. Then, pulling Woodchuck’s hairs from her belt, she made a game-bag out of her own hair. Gluskabe was glad, and he thanked her. Then he went into the woods and called for all the animals to come near. He said to them, “come on you animals! The world is coming to an end, and you animals will perish.” Then animals of all kinds came forth; and he said to them, “get inside my bag here! In there you will not see the world come to an end.” Then the animals entered the bag, and he carried it to his wigwam. Gluskabe said to his grandmother, “I have brought some game animals. From now on we shall not have such a hard time searching for game.” Then Woodchuck went and looked at all the different kinds of animals that were in the game-bag. She looked at Gluskabe and said, “you have not done well, grandson. Our descendants will in the future die of starvation. I have great hopes in you for our descendants. Do not do what you have done. You must only do what will benefit them, our descendants.” Gluskabe heeded his grandmother. He went back into the woods and opened the bag, and said to the animals, “go out! The danger is gone. Go out!” The animals scurried out of the bag and scattered off.

VM: And so you were able to stick to your interpretation of the stories?

CB: Yes. In art school, of course, doing that might affect your grade depending on the teacher. There are definitely some teachers who focus more on how your artwork turns out aesthetically, and want your techniques to be really good. There are other teachers who would rather push content in your work, making sure that you have solid reasoning behind your art. One of my professors who pushes for content really inspired me to start doing art related to my family’s heritage and the stories I heard growing up. Because whenever teachers push for content I usually turn to my family, my heritage, and my own personal experiences to create meaning in my art.

VM: That actually brings me to my next question, because the Cherokee piece that you mentioned earlier came not from you reading about it online but from a personal interaction that led to it. So the next question is, how have you been influenced by other Native people either in your tribe or in other tribes, and even non-Native artists?

JB: I’ve been influenced in a tremendous amount of ways and I continue to steadily be influenced in a tremendous amount of ways. Really it started with my mother. My mother used to work for DoubleDay Books and she would work with the artists who drew the artwork for book covers, and she would do the artwork sometimes. So she would come home with these amazing sketches that were of Native people. I remember very specifically a sketch of a guy who was kind of squatting down holding a pot in front of him, a small, small vessel in front of him. And I thought it was the most incredible piece of artwork. Not only was it well drawn, but I hadn’t really seen Native people portrayed in art like that. Even at powwows back then you didn’t really see a lot of artists selling paintings, or at least the powwows I was going to, you didn’t see paintings and drawings. There were tons of amazing clothing, and traditional craftwork, but you didn’t really see paintings. And when you did, it was very rarely contemporary stuff. As far as non-Native artists go, I wasn’t ever really taught by any Native traditional artists. I wasn’t trained in learning how to draw. I learned from my art teacher in high school. I learned from watching TV artists, from growing up in New York in the ‘70s and ‘80s. I learned from seeing Bob Ross! Things like that. So the influences for me, were taken from those two different areas. There was the art from Native people that placed Indigenous people and concepts at the center, but the formal training came from outside that space and from my mom bringing home book covers or comics. I would draw superheroes! And now I see other artists mixing these influences, like the artist from the Pacific Coast, Andy Everson, who does contemporary art with traditional ideas – taking the Pacific Northwest Coast designs once used for masks and clothing and using them to depict, for example, the Starship Enterprise or Yoda, using the juxtaposition of Native imagery with contemporary subjects and issues. So myself and others have been influenced by each.

VM: And do you play with pop culture in your own work?

JB: Yeah, I think I do, in subtle ways. I don’t ever consciously try to make it the forefront of the ideas I work on. Some of my work was displayed at a fundraiser called Hip-hop 4 Flint, in Providence, and I did a couple of pieces that revolved around what was going on with water pollution. One of the pieces which was called “Water Gun 2016 FS”, is a guy with a gun against his head, and it’s a water gun, and it’s filled with dirty polluted water. The bullet coming out of his head on the other side is also made of the dirty water. It’s reminiscent of blood, so that was sort of a cultural reference to both gun violence and water pollution in minority communities using some pop culture imagery. Another one I did confronts the image of the American flag where I attempted to show that our country has been suffering, not due to outside forces but rather our refusal to look after our own citizens. But I make my art without the intention of having to implant pop culture references for others to see and recognize; I use them to create subtext and layers of meaning that aren’t necessarily always acknowledged

VM: And Christiana, since you’re an art student, you’re probably surrounded by art students and teachers almost constantly. How do they influence your work?

CB: Yes, there are a lot of classmates of mine who inspire me when I look at their artwork or watch their techniques and methods, but also in going for an art degree one of the things I always try to do is never copy someone else. And among the artists I know, everyone has that mentality of not wanting to do exactly what someone else just did. You want to have your own twist, or make it better, so I never copy others but I do get inspired by them. I’ve appreciated learning from my teachers, especially my print making teacher. I really enjoy making prints because of the multiple techniques and mediums you can work with. As for art history, it’s never been my favorite class but there are some artists in the past who I am drawn to, and I like to learn what mediums they used and read their artistic statements. I’m most interested in why they created it and how they created it, as opposed to looking at and enjoying the piece. Whether it’s an artist from the past or a contemporary art creation video online, I always look at the medium and techniques and think of how I could use it for the art I want to make. Could I use that, if I wanted to?

VM: Taking the medium and putting it to your own ends, so to speak.

CB: Yes, definitely.

VM: Christiana, you certainly use a lot of different methods in your art. You’ve done paintings, drawings, pen and ink, woodblock, even beadwork. And Justin, you also do drawing and digital art and you’re involved in music, everything from recording hip hop to powwow drumming. How do these different media forms interact with each other and on each other for you?

CB: I think the artwork I’ve been doing lately relates really well with storytelling because the artwork is literally coming from the content of the stories. I also did a piece that would actually relate well to video and drumming. This piece was for an assignment where “personal ritual” was the theme, so I took a canvas and my partner and I put paint on our feet and we did an Eastern social dance on the canvas. I didn’t know any drummers in my school’s area well enough to have them come in person to sing, so we found music online from a drum group we knew well and used that as the song. I set a round stool in the center to represent the drum, and taught my partner this dance because he didn’t know this one. On the final piece, you can see all of our footprints on the canvas from where we danced. Creating the piece took not only the relationships between different mediums – the video on youtube, the canvas and paint, the dancing – but also the relationships between myself and others.

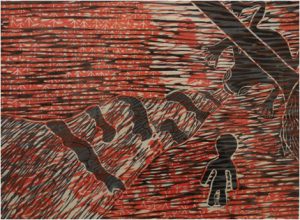

Water Famine, Christiana Becker

Water Famine is the creation story of the Penobscot people. The story goes, Gluskabe noticed that his people were looking sickly and investigated the matter. Gluskabe discovered that his people were dying of thirst by a monster frog. This monster frog was drinking all the water and refusing to give any water to anyone. Gluskabe went to the monster frog and asked for the water back. Once the frog refused, Gluskabe picked up the frog and broke his back, but that wasn’t enough for the frog to let go of the water. So Gluskabe took his ax and chopped down a yellow birch tree that killed the frog. Out of the frog’s mouth rushed the water. The people, as thirsty as they were, dove into the water and some of them turned into turtles and frogs, forever becoming a part of the river. This water became the Penobscot river.

JB: The influences in the music that I make relate back to the Native aesthetic conversation. For example, in powwow drumming there’s a certain sound, there’s a specific way notes are used in terms of order. Things don’t jump from this place to that random place over there. So when I make other music, that’s something that I’m aware of. I’m aware that these things, these particular patterns for melodies or rhythms, help differentiate different styles of music.

VM: So the particularities of powwow drumming have really made you aware of form in all types of music.

JB: Right, right. And how those forms fit together, and where they intersect. Across the board, whether it’s visual art or music, it’s allowed me to sort of push the boundaries, to push the lines between things in a way that is new but feels natural. In terms of influences for music, I’m influenced by local powwow drums too, like Mystic River, Storm Boyz, Rez Dogs… there’s a fair amount of groups that have influenced my ability to write powwow songs. And most artists tend to incorporate bits and pieces from other artists that they like – not necessarily outright copying, but the more you know, the more capable you are. So the more rock, or blues, or classic music you listen to, the more your abilities grow because you have more to draw upon. The same applies to art. I try to look at all different kinds of visual art, whether or not I like it since that’s entirely subjective, and the next time I make something it may be influenced a bit by those pieces. I do try to seek out other Native artists largely because they are not necessarily given the same attention that other artists are. I believe that when people hear “Native” or “Indigenous artist” they put that art in a certain framework, mentally, and it becomes this niche for some people. But for other people it doesn’t make a difference, not in that way. So my influences come from a space of being aware of as many different forms as possible, so that I can push the boundaries of those forms in a way that at least I personally haven’t seen them pushed before. And if you can see the boundaries being pushed in one medium, it can also inspire you to push the boundaries in another.

VM: Being inspired across mediums, it seems like one piece of art could not only lead to another, but two pieces of art might even co-create each other in a given moment in time.

JB: Absolutely. I often do music videos of my art, where I pair my art and my music recordings together. Sometimes that means listening to a song and figuring out which of my paintings and drawings go with it to create a certain effect, but other times I look at a piece of art and try to express musically what that piece makes me feel and think. You could show two people the same piece of art and play two different songs for them, and they might come away from that painting with radically different interpretations of it; or you might look at a piece of art and get one feeling from it, and later come away with a totally different feeling. And that’s what’s really exceptional about art, even if we expand the concept of art to include the art of throwing a ball, the art of someone playing with their children, the art of serving food. You might see it, and there’s something about it that strikes you and inspires you in some way. It makes you want to go do something. I makes you want to create, or to go call your mom. It makes you want to go to an animal shelter and adopt a rescue. There’s an art, and a beauty, in all of that, throughout our lives, and everything is influencing the things around it down to even an elemental or atomic level. Things are always interacting, and influencing, and pushing and pulling against each other. Art allows us to be aware of that.