We need to face the fact that this country was built on the bodies of Indian people—indeed, there was a holocaust on these shores. Once we know our country’s history, we can work to improve policy and practice. Then and only then will we be capable of empathy with other countries and cultures. Then and only then will we be prepared to look outside our protected shell and actually help other countries. Then and only then can we start building a new legacy of respect within the global community. The struggle to educate and be educated continues.

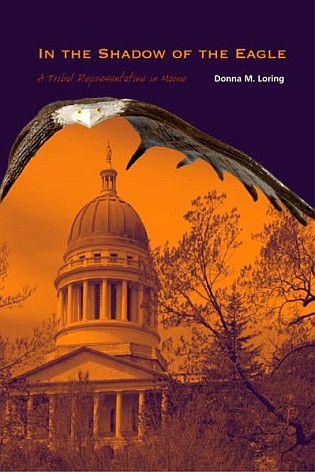

Donna Loring, In the Shadow of the Eagle: A Tribal Representative in Maine

Donna Loring sheds light on a variety of issues—Native and non-Native—throughout In the Shadow of the Eagle. Spanning three years, 2000-2002, Loring shares the many intricacies of politics from her perspective as the representative for the Penobscot Indian Nation in the Maine legislature. Through these genuine, thoughtful, and informative journal entries, we learn how little attention is truly paid toward issues concerning the Wabanaki of Maine and other tribes across the nation.

Loring tackles many issues throughout the time periods her journals highlight, beginning with the Offensive Names Bill. This bill effectively cut the word “squaw” from public use—just as any other word considered offensive toward women or a class would be. What was most surprising was not only that a bill such as this was needed within the past decade or so, but also that there was a great deal of opposition to its passing. In one particular instance, Loring recalls a home-run moment as she voiced her reasoning behind her support of the Offensive Names Bill toward a local business owner: “Do you feel guilty earning money from a name that is abusive and dehumanizing to Native people?” (26). Assertively, Loring calls out the ignorance still prevalent in present-day New England in that Indians and their history and culture is little more than an artifact to be remembered for tourism purposes. Luckily, this attitude is certainly changing, and Loring is a driving force behind the transition toward equality.

The effort to create enough support for this bill was immense, and yet as soon as this victory was accomplished, Loring was hard at work yet again. The tribal legislative representative has some influence in committees, but cannot vote. Because this position is on the unique side (Maine is the only state to have tribal representatives in its legislative body), there are no other models of representation on which to base any restructuring. Unfortunately, Loring was not able to gain a vote within the committees or any other legislative level. Along with this, any mention of Indian-run casinos (or even paying less fees for bingo games) is practically the equivalent of yelling “Fire!” in a crowded theatre to the Maine legislative body.

In spite of these setbacks, Loring was able to help create and draw support for a bill requiring the teaching of Maine Native American history in the K-12 educational system that is created with input from tribal members and historians. This is a huge deal, as it will lead to a whole new generation of respect and understanding for the culture and history of the Maine tribes. As Loring aptly describes this bill, “They will come to know who we are and know our struggles and our accomplishments. We will become real human beings to these children and they will honor Maine’s first people when they become adults” (253).

Loring’s honest accounts of her struggle to represent the larger issues of Native rights—“Native rights” being an umbrella term covering environmental, educational, social, gender, legislative, and other factors—sheds light on issues that are so often swept to side or put on the back-burner for other issues that may or may not report better to the majority audience.

Her journals are one more way to enlighten the world at large—especially New England. Loring’s open and genuine reflection makes it impossible not to follow even the most complicated political explanations. This paired with the hard-hitting action and well-articulated speeches concerning many of the different issues mentioned make for a great, informative read that will quickly bring you up to speed on Maine politics concerning Wabanaki rights and issues.

Renee Poisson is a Senior majoring in English at the University of New Hampshire.