On Wampanoag Clothing in Native Fashion Now

by Elizabeth James-Perry

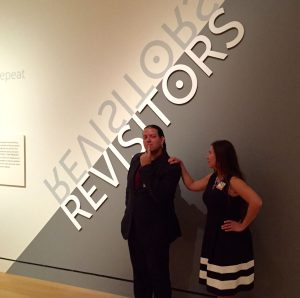

I would have to conclude, after this playful photograph was snapped at the November 2015 exhibit opening, that my brother and I are indeed, Re-visitors. My Aquinnah women’s outfit in Native Fashion Now, Peabody Essex Museum exemplifies the way trade materials such as linen, sterling silver and German silver were incorporated seamlessly into Native fashion more than 2 centuries ago, blending here with a wampum alliance collar and woven quill cuffs. With a strong background in traditional textiles, from harvest, spinning, weaving and dyeing, it’s the weight of threads, the directions they move in-and the fabric they describe that matters to me. Contrasts accentuated by red pay homage to a traditional Wampanoag palette, while there is a conscious effort to add movement by employing a blanket width piece, to create a double layered skirt, and add a cape to the blouse. The oblique sash is based on a gem from Nantucket.

I would have to conclude, after this playful photograph was snapped at the November 2015 exhibit opening, that my brother and I are indeed, Re-visitors. My Aquinnah women’s outfit in Native Fashion Now, Peabody Essex Museum exemplifies the way trade materials such as linen, sterling silver and German silver were incorporated seamlessly into Native fashion more than 2 centuries ago, blending here with a wampum alliance collar and woven quill cuffs. With a strong background in traditional textiles, from harvest, spinning, weaving and dyeing, it’s the weight of threads, the directions they move in-and the fabric they describe that matters to me. Contrasts accentuated by red pay homage to a traditional Wampanoag palette, while there is a conscious effort to add movement by employing a blanket width piece, to create a double layered skirt, and add a cape to the blouse. The oblique sash is based on a gem from Nantucket.

In making the Alliance collar and long wampum earrings, I considered pivotal moments our woven wampum has born witness to. For example: the roll that 30 wampum collars played in Huron fate -they were wagered in a game designed to improve their Nations’ luck on the eve of war with a nation to their west. How a contemporaries’ account of Pometacomut’s War concluded with the deep purple star medallion and massive Nation belt being turned over by a Wampanoag war captain in the 17th century. Or reading an account of a beloved Lenape woman far from her original homelands, who was laid to rest wearing 7 wampum collars graduated in size, and wampum mittens [gauntlet cuffs], at the close of the 18th century in a funeral attended by Heckelweider.

With its renewed popularity, wampum adorns the casually dressed New Englander, who simply appreciates the rich color and the people who work the shell. It is also part of formal ceremonial attire and traditional Native dance wear. In my short life, I have seen other ways wampum is still intertwined with our lives: Facing the distinct possibility that an industrial wind turbine farm was going to be placed over a sacred site and viewscape, I donned a contemporary shell medallion to explain the origin of that star motif in a tribal meeting with the Advisory Council on Historic Preservation; more recently my Mother Earth and Bear pendant was gifted to President Barack Obama by a Mohegan tribal leader.

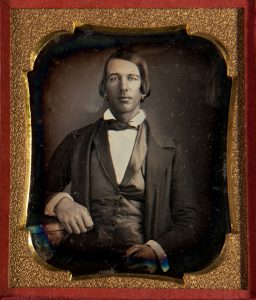

Thomas S. Boston, a 19th Century Wampanoag Musician

by Elizabeth James Perry

Every five years or so some unusual museum object, artwork or circumstance will warrant my serious attention. I made the acquaintance of this figure around the winter of 2012, a daguerreotype (early high quality form of photography on silver coated metal plates circa 1839 forward) listed on EBay, labeled “Wampanoag Indian Whale Man from New Bedford.” A colleague and Aquinnah tribal member on the Vineyard had brought the EBay advertisement to my attention, after having spotted the actual daguerreotype in a New Bedford antique shop. The unidentified gentleman was distinguished-looking with an intelligent gaze, perhaps in his twenties. Though obviously not a contemporary of mine, there was a familiar quality to the person.

Slightly suspicious of antiques said to be connected to whaling or whale men due to the exorbitant market prices for such things, nevertheless I was curious. I settled on a tedious methodology to prove or disprove the label: list out every Native man with the occupation of mariner in the Earle Report, (an 1860 census in Massachusetts by the Commissioner on Indian Affairs John Milton Earle), then compile other whaling records and go from there. But life is full of strange chances. Late in the evening of Research Day One this entry stood out: Thomas S. Boston, age 21, member of the Dartmouth Wampanoag tribe, residing in Westport, occupation: Daguerreotypist. Reference librarian Paul Cyr New Bedford Public Library helped to locate a historical newspaper article that gave his name as Professor Boston, a title used by musicians. That description seemed to fit the person in the daguerreotype; slim in youth, and with the same piercing eyes that I noticed in many of our tribal ancestor’s visages, nevertheless, he did not strike me as someone exposed to the dangers of life spent whaling. We located his older brother Oliver Cook Boston in a New Bedford, MA city directory, residence 226 Middle St. Both brothers were listed as teenagers on ancestry.com as waiters in a census. They were in the Nantucket militia in 1857, they enlisted during the Civil War; with Oliver joining the Navy and Thomas furnishing a substitute in 1863. Oliver married in March of 1862.

I recalled reading brief biographical sketches including one of Thomas Smith Boston in Frances Karttunen’s The Other Islanders: People Who Pulled Nantucket’s Oars. He was trained as a barber, and recognized on Nantucket as a talented violinist, who I speculate, found many opportunities to play at Pompey’s dance hall. Following the death of his parents, Thomas departed the island at age 19 for better employment and educational opportunities; many tribal members left Marthas Vineyard for the same reason in the 19th century. In 1857 Thomas worked for Phillips, Sampson & Company book publishing in Boston, Massachusetts; by 1859-1860 he was listed in the Earle Report as living in Westport. Presumably he was living with Oliver Boston, or perhaps with Cook’s, Wainer’s, or Cuffe relatives in the town on a temporary basis. As chance would have it, scrutinizing old maps of circa 1850 Dartmouth on a different errand, I caught sight of the label “Mrs. Boston” on a tiny dot near the Padnaram harbor that I imagine was once his mothers’ property. There was an 1860 newspaper ad for T.S. Boston Daguerreotypes, at Cady’s, 343 Canal St, New York, NY; according to Craig’s online daguerrian list James Cady worked in New York City 1858-1860.

The Other Islanders contains some contemporaries’ physical descriptions of Thomas Boston as “light skinned, fastidious about his appearance”, and a slightly later Washington, D.C. newspaper article as “dressed in the height of fashion and the color of java coffee.” Looking at the daguerreotype, the physical descriptions seemed pretty close.

A close look at the portrait said to be of Captain Absalom Boston that graces the wall of the Nantucket Whaling Museum reveals -to my artist’s eye- certain facial traits in common with the daguerreotype portrait: witness the shape of the eyes and the lines around the mouth. The painting was donated by the Pompey family at the turn of the century. The gold earrings worn by the daguerreotype subject could have been inherited from his father. Influential community leader Absalom Boston (1786-1855) of Nantucket descended from a sea-faring family. He was a merchant with businesses, a meetinghouse/school and house on York Street. Still extant, the meetinghouse is now the Nantucket Meetinghouse Museum built circa 1827. Absalom’s parents Seneca Boston and Thankful Micah built the adjacent home just prior to the Revolutionary War. Hannah Cook (ca. 1795-1857) was Absalom’s third wife; she came from the Dartmouth Wampanoag community on the mainland. They could have met when Absalom shipped out with a George Cook (Nantucket Historical Association on-line database), or through other associate’s and kin in the Wampanoag and African American network of men and women working in whaling and shipping-related industries.

I seldom journey out to that farther island in the Atlantic, but in 2008 took the fast ferry to Nantucket, in order to attend an evening lecture about archeology around the Seneca Boston house. There I was befriended by the late Director of the Museum, Rene Oliver and her husband Bill. It was a chilly, dreary, end of October but I recollect the meetinghouse was pleasant inside, and my hosts acquainted me with the history of the neighborhood. Bill shared his experiences as a civil-rights minded school teacher from Texas with us over breakfast the next morning. My intention at the time was to return and look into early Nantucket Native community records.

The Boston’s were people with high ideals and convictions who led the Nantucket abolition movement with the Pompey family and forced the integration of Nantucket island public schools. During a lecture I attended at the African American Meetinghouse in Boston, Massachusetts, the authors of Picturing Frederick Douglass pointed out an important trend in employment among 19th century abolitionists as professional photographers. In entering this field, 19th century activists were using the camera to humanize marginalized subjects, a brilliant strategy. That may have been part of the draw for Thomas Boston in the late 1850’s. I do not have as many details as wished for regarding his early career, however during the last half of the 19th century both the New England Music Conservatory and the Boston Music Conservatory in Massachusetts admitted Native American and African American students; out in Ohio, Oberlin Conservatory was involved in the Underground Railroad.

T. S. Boston was well-traveled during the Civil War and more so during Reconstruction. He was a Massachusetts delegate to the National Convention of the Colored Men of America on January 13, 1869 held in Washington, D.C. along with F. G. Barbadoes, and Richard Smith; the lengthier list of New York delegates included Frederick Douglass, and his sons Frederick and Lewis. He invested in the Douglass Brother’s newspaper the National New Era with Harvard graduate Richard T. Greener in the 1870’s. Those were exciting times, when groundwork was being laid for better human rights, women’s rights, equal educational –and business- opportunities. I do not consider Thomas as out of his element, due to his own intelligence, and hard work, and his Massachusetts Wampanoag families’ business acumen and activism.

Thomas Boston married Anna M. Wilson in a high-profile wedding, October of 1869 and visited family in Massachusetts according to Nantucket’s Inquirer & Mirror; and they were associating with some of the intellectual activists who created Howard University. His “affable manners”, appearance, and musical talents on the piano, organ, melodeon (a mellow sounding small reed organ developed in New York) and violin were noted frequently in the newspapers, where his regular advertisements offered music and dance instruction. T.S. Boston had worked for the U.S. Treasury Department, then both Boston and his father-in-law Professor William Wilson worked at Freedman’s Bank during Reconstruction. After leaving Washington D.C. sometime around 1878, he moved west obtaining a degree from the Chicago College of Medicine in the early 1880’s; he practiced in this profession a short time, whilst continuing his musical career.

Serious musicians often allied with high-quality producers of musical instruments. In Chicago, T.S. Boston worked for W.W. Kimball Piano Company, the largest music house in the west; and as a traveling agent for the Western Branch of Hamlin & Mason Organ and Piano Co. for about 10 years from 1883 onward. Favorable reviews of Professor Boston’s recitals appeared in newspapers such as the Douglass Monthly, Inter Ocean, the Washington Bee, the New York Globe, Chicago Daily Tribune and The Appeal from St. Paul Minnesota and the Janesville Gazette in Wisconsin. The newspapers notices served as a way for me to chronicle his piano solos and performing groups -bands, quartette’s, double quartette’s and jubilee singers -and performance venues; places like Weber Music Hall built by Weber Piano Company, Farwell Hall, McCormick Hall, Garfield Hall in Ohio, the piano rooms of H.M. Brainard & Co., Avenue Hall, St. Paul’s Chapel, Quinn Chapel, Chicago Avenue Church, and the Metropolitan Church and Fifteenth Street Presbyterian Church in D.C., as well as Music Schools.

Accessing much early published music posed a challenge; due to limited staff time, many 19th century sheet music collections remain uncatalogued. To date, I have located one temperance song by T. S. Boston for the piano published by The Root & Sons Music Co. in 1878, probably the same business as E.T. Root & Sons advertising in Chicago’s Blue Book, offering violins, guitars and mandolins; both my mother and a librarian suggested he may have published music under a different name. Alternatively, he may have sold songs to other performers. Whatever the case, more than one newspaper article mentions the names of his compositions -some serious -others humorous, among them Gavotte, The Laughing Song, Transposition of the Sweet Bye and Bye, The Old Brandy Bottle, Smiles & Tears. Some were his own arrangements of popular aires.

As his career progressed, Boston was called “one of the finest pianists of color in the country,” and as being an “American Josephy.” A very favorable comparison: Rafael Josephy was a brilliant 19th century Hungarian-born composer and pianist who performed with the New York Philharmonic Orchestra. The New York Age featured a retrospective about George E Barret, of the Fisk Jubilee Singers, and his performance with Boston in an operatic concert in Baltimore, Maryland. The author describes Boston as “the foremost baritone in Washington, D.C.” No exact date was given; it can be inferred as falling somewhere between 1874 and 1878.

One of the earliest references shows his versatility in filling in during a winter storm: The Weekly Anglo-African November 26, 1859 mentions “…a series of grand musical entertainments…by the Anglo-African Musical Union at the Metropolitan Assembly Rooms on Prince St.,… Madame Luca and Prof. T.S. Boston’s splendid vocal and instrumental performance.” A column the Christian Recorder termed Arrivals at Mrs. Hasikerson’s Boarding House, 21 Green Street, NY for Oct 26, 1867 included not only T. S. Boston of Washington D.C., but also Mrs. Elizabeth T. Greenfield and Troupe of Philadelphia, PA; legendary international singer Elizabeth Taylor’s career began in the 1840’s. She was nicknamed “the Black Swan.”

An 1884 copy of the Cleveland Gazette offered this description of T.S. Boston’s “voice being a baritono robusto projundo, with a special adaptation to the recitativo. Consequently, it’s a very able voice, and was greatly admired.” During his month-long trip in March of 1888 to the Nations’ capitol after a 10 year absence, Professor Boston’s “brilliancy of touch and power of expression…” were remarked upon following his reunion concert in the New York Freeman. T. S. Boston was listed among the prominent residents, businessmen and artists in the 1892 Chicago’s Blue Book under Orchestra, for piano and vocals out of the Chicago Music Company. He participated in the 1893 Chicago World’s Fair, as an invited dignitary during Frederick Douglass’ opening of the Hayti Building.

Unfortunately, his marriage to Anna seemed to have been a casualty of financial strain following the Freedman’s Bank collapse in Washington, D.C during the recession. The couple however, may not have sought a divorce, and did occasionally perform together in D.C. I never found evidence of Anna Boston living with Thomas after he moved to Illinois; she appeared to stay in the vicinity of D.C., working as an educator. It is not clear whether Thomas visited Massachusetts much; after his brother died of consumption in 1872, he did not seem to have many close family members left.

Boston gave performances with a number of highly regarded musicians, including, Madame Lucy Adger and Mr. Samuel Adger, Mr. Frederick Haynes of Boston, Pedro T. Tinsley, Mr. Soeffler, the celebrated baritone of the famous Chicago quartette, and Miss Ida M. Platt, a fine musician who would soon become the first woman of color to pass the bar in the state of Illinois. I do not know all the details of Boston’s connection to the Platt’s. It may have simply been a friendship, or that the elder Platt was connected in some way to Absalom Boston when the family lived in New York. T. S. Boston was the president of the Les Enfants social club of Chicago, and of the Colored Men’s Liberty Association that held an honoring banquet for Honorable John M. Langston at Quinn Chapel A.M.E. Church and the Palmer House. He was a “foreign dignitary” at the Grand Royal Arch Masons gathering in 1891 of the Illinois, Iowa and Jurisdiction, when his sketch showing a mustache and shorter hair, possibly drawn from a photograph, appeared in the State Capitol Newspaper. Often he was listed as the director of a given concert, a prestigious position that provided better pay.

T.S. Boston put on benefit concerts for hospitals, churches, and participated in charity balls, appearing in “full dress, hair a la pompadour, in diamonds.” Sadly, Boston died at the relatively young age of 55 on November 19th, 1893 after suffering a stroke. He was laid to rest in Graceland Cemetery in Chicago in the Platt family plot, where the Russian ambassador and professor Richard T. Greener was interred decades later. A brief obituary noted that prominent Reverend David Swing of Quinn Chapel delivered a moving eulogy. T.S. Boston’s personality, and music seem to have been missed; one retrospective recalled with fondness “Professor Boston’s Assembly dances” while lamenting fewer opportunities existing for pleasant gatherings among early 20th century Chicago society. Did they know they were missing the classical music of an island Wampanoag composer?

Elizabeth James-Perry, Aquinnah Wampanoag tribal member of Massachusetts is a life-long traditional artist, taught by family and community. She has conducted research in the Northeast as well as in Europe. Her work focuses on the finest Northeastern Woodlands Algonquian material culture including wampum shell adornment and diplomacy, and endangered arts such as: textiles, woven quillwork, indigenous plant cultivation and natural dye techniques. She has a dual background in art and science, with coursework at Rhode Island School of Design, and holds a degree in Marine Biology. An inheritor of a complex legacy as a Native whaling descendant, Elizabeth has fond childhood memories of observing her mother’s careful hand as she carved scrimshaw. Elizabeth recounted some of her families’ history for Nancy Shoemaker’s book Living with Whales, and was a 38th Voyager onboard the Charles W Morgan. She exhibits her art nationally and is a recipient of the Rebecca Blunk Award in 2015.